Doctoral candidate Xin Yu explains how genealogy books enabled their authors to establish political power in early modern China.

For historians, genealogies have long been essential sources of information about demography and migration. New research by Xin Yu, a doctoral candidate in history at Washington University in St. Louis, argues that as physical objects genealogy books have enabled their authors to establish political power.

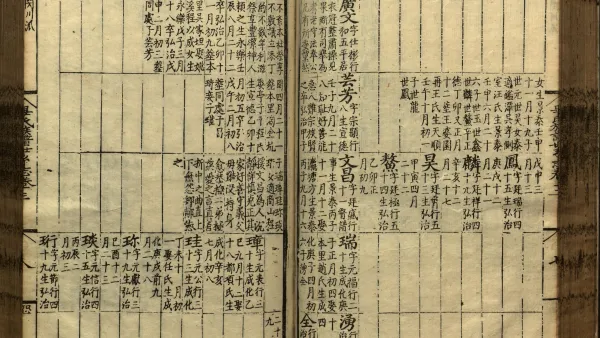

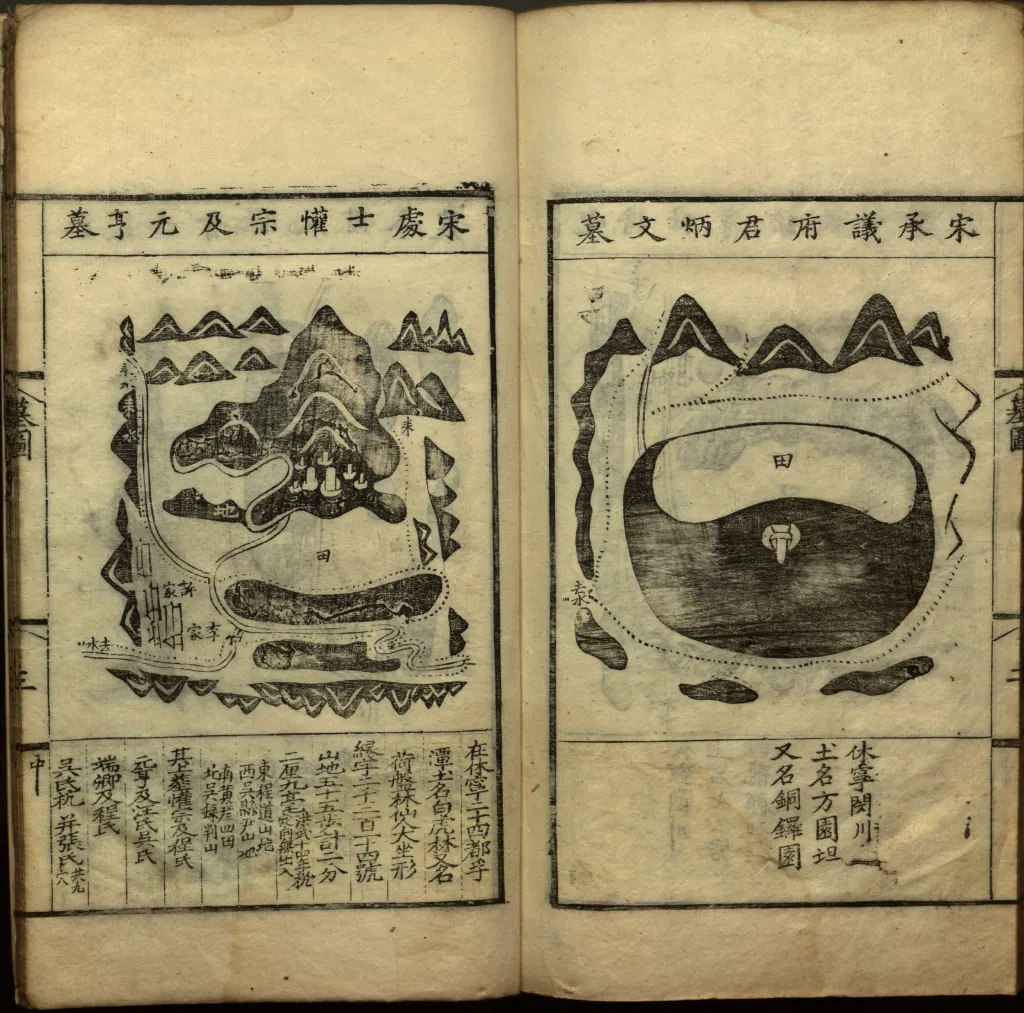

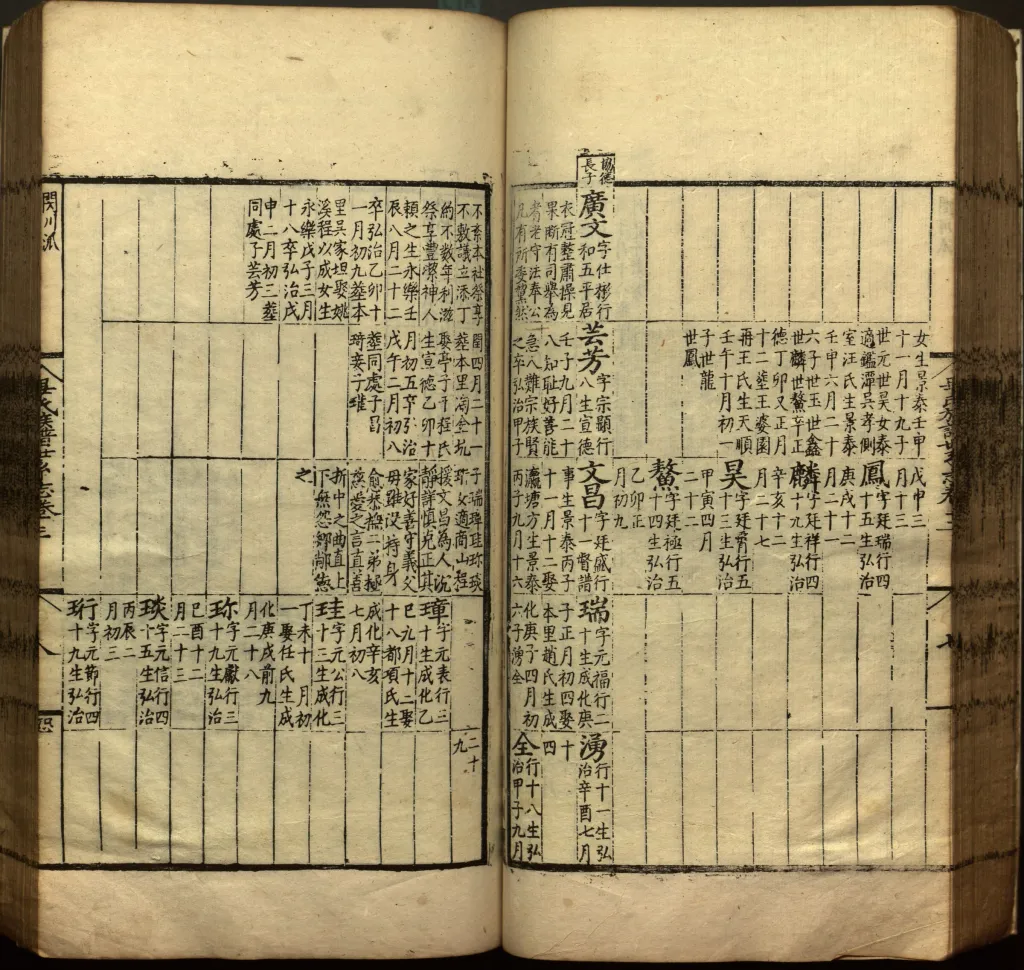

Genealogies are often mined for the valuable information chronicled in them. Yu observed that in the context of 16th- and 17th-century China, however, “genealogies are not simply family history.” They also contain materials and ephemera that might seem surprising today. “These books include all kinds of different materials,” he said, “including biographies, illustrations, maps of villages, and appended legal documents like land deeds and lawsuit papers."

These elaborate compilations were produced by members of an educated elite class as a way of establishing power through narrative. The authors “assume the leadership of the lineage they came from,” Yu said, "while also gaining fame in local society and accumulating political capital for their career. Genealogies were political objects in the sense that they were products and producers of power relations, both in bureaucracy and in society.”

China in the 16th-century was undergoing a period of political chaos, marked by weak emperors and rampant corruption. Establishing one’s lineage was a way to create order out of that chaos. Writing a genealogy was an act of political theater. “By compiling genealogies,” Yu said, “China’s educated elite could perform their competence, demonstrating to those that they would govern that they are qualified public officials because of the way that they honor their family.”

These new genealogical practices were made possible by technological innovation. Earlier Chinese genealogies were manuscripts, but by the 16th-century genealogies were often printed in runs of up to 200 copies. The book was an object of veneration, Yu said, “typically preserved in a dedicated box that would be hung from the beam of the ancestral hall. People would see these boxes of genealogies when they came to the ancestral hall to venerate their ancestors, and so the genealogy becomes associated with the rituals of ancestral worship.”

The discovery that genealogies functioned as objects of veneration in this way lead Yu to challenge the established interpretation that they were written only to be read by a literate elite. Instead, Yu argues that “most of the people who ‘read’ these genealogies were illiterate or at least had very low levels of literacy. Even if the language contained within these books was archaic and sophisticated, people could still understand the political meaning by looking at the illustrations and by regarding the genealogy as an object of public veneration.”

Through his research, Yu is hoping to change the way that historians understand genealogies by demonstrating that they are more than containers of information to be mined. The genealogy is an important genre whose form, structure, and reception history can illuminate the ways that political authority is established. To better understand the evolution of the genealogy as a genre, Yu employs large-scale digital methodologies. "Like any historian," Yu said, "I conduct close analysis of a selection of genealogy texts, but, in addition to that, I also rely heavily on digital methods to make sense of the over 400 extant genealogies produced between 1500 and 1644, potentially an ideal dataset for distant reading and text mining. "

Xin Yu is a fourth-year PhD student in history at WashU. While writing his dissertation, he is also building three databases: Reasons for a Genealogy, Social Networks of Genealogy Contributors, and Images in Ming Genealogies. For more information, visit his website.