Graduate student Heesoo Cho wants to challenge the idea that only scientific and commercial knowledge contributed to how people understood the Pacific Ocean in colonial America and the early republic.

Imagine it is the late 18th or early 19th century and you’re dropped onto the grainy beach of one of approximately 25,000 Pacific Ocean islands. You decide to write a letter to a hypothetical rescuer, but you have no idea how many islands exist, and you need to distinguish your island from all the others. How do you begin orienting yourself and the island in relation to one of the globe’s largest bodies of water? How would you describe your location so someone could find you?

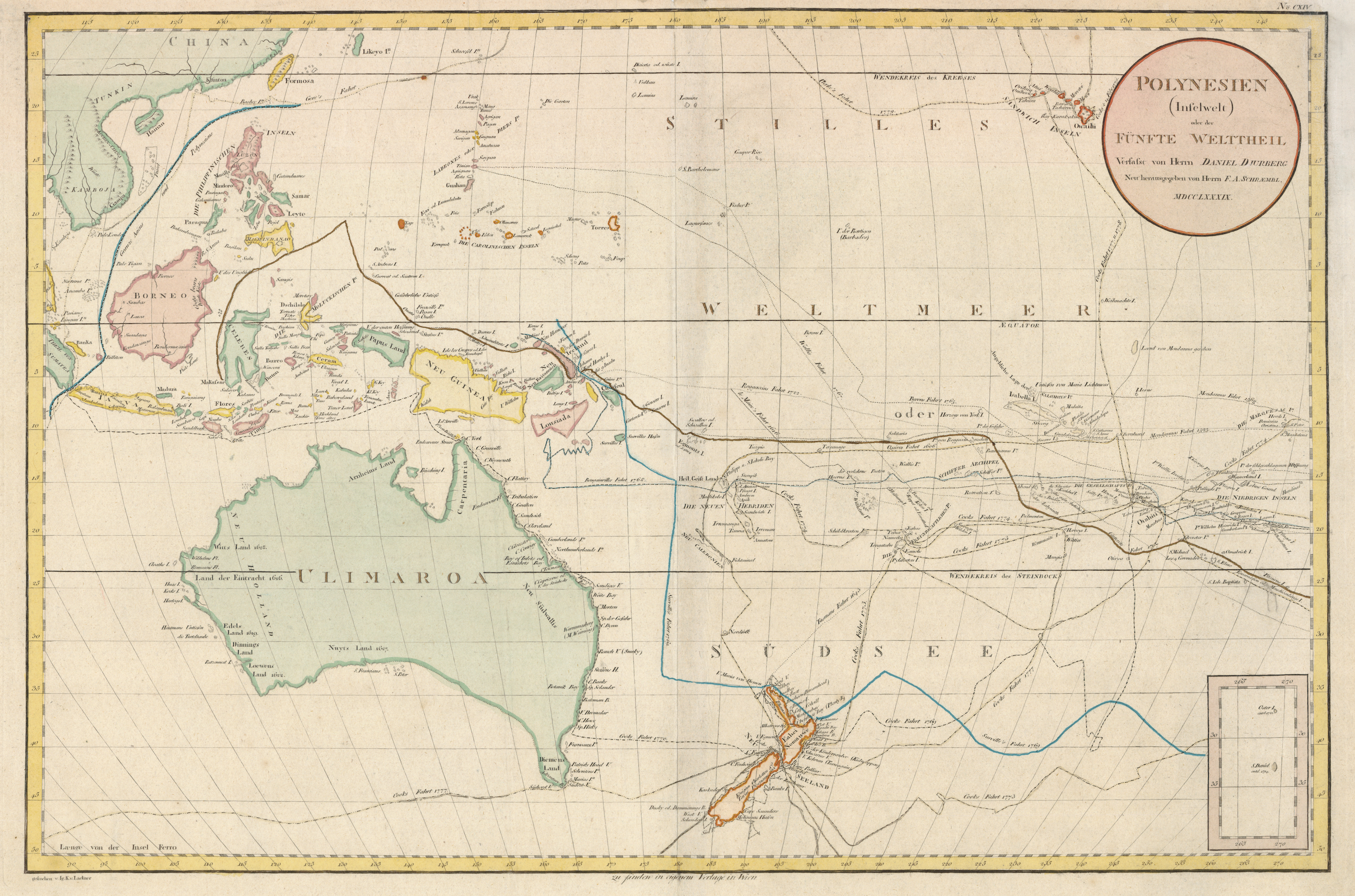

Describing geographical spaces involves also categorizing those spaces. For example, even just the simple act of differentiating land from water introduces an artificial border between the two. How people have historically grouped these spatial forms informs doctoral candidate Heesoo Cho’s research. Her dissertation, tentatively titled “The Making of the Mental and Material Map of the Pacific in Early America, 1740–1820,” examines the social and cultural construction of the Pacific Ocean in colonial America and the early republic.

Through reading maps, journals, logbooks, newspapers, and private correspondences, Cho explores how different forms of communication and mediums of knowledge exchange conditioned and expressed understandings of the Pacific in this period. Rather than framing the Pacific as an already-coherent space, Cho argues that early Americans viewed the Pacific as disjointed and mutable, its contours varying according to the political climate, the needs of commerce, and the material realities of the age of sail.

Cho, who received her undergraduate degree in her home country of South Korea, explained that her interest in early American history grew out of her one-year study abroad experience at the second oldest higher education institution in the United States, the College of William and Mary. Chartered in 1693 and located mere steps away from Colonial Williamsburg, William and Mary is the alma mater of several famous early American figures, including Thomas Jefferson and James Monroe. But Cho quickly gravitated towards studying the perspectives of people who lack representation in America’s founding story. “I first studied indigenous and African American history while there,” she said. “Back in South Korea, American history is white American history.”

When she returned home Cho completed a master’s thesis on Daniel Webster’s nationalism, but she never forgot about her studies of the formation of early America. Cho eventually applied to WashU to work with Peter Kastor, professor of history, who is interested in framing the history of colonial America and the early Republic outside of predetermined national and geographical boundaries. “We are both motivated to move past the limits of boundaries,” explained Cho, “so eventually I chose to come here to study with Dr. Kastor, and honestly I think it is one of the best decisions I ever made.”

Cho cited the ability to explore her own passions as one of the strengths of WashU’s program. This flexibility allowed her to read seminal works such as Silencing the Past by Michel-Rolph Trouillot and Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive by Marisa Fuentes. Both Trouillot and Fuentes focus on how to responsibly write about the perspectives of marginalized groups when the evidence does not exist in traditional archives. Inspired by how they employ a wide range of methodological approaches and uncover alternative narratives, Cho is quick to highlight whose voices are missing from her reconstruction of the Pacific.

“This mapping is an incomplete picture,” she said. “The materials that help me make an argument that early Americans thought about the Pacific Ocean in a disjointed way emerges from the archive. But what compromises archives is very selective, and archives are purposefully designed to neglect certain voices: people who are enslaved, indigenous populations, sailors.” These groups all bore some familiarity with the Atlantic Ocean, a body of water which often recalls the horrors of the Middle Passage. By incorporating an emphasis on the Pacific, Cho hopes to contribute a slightly different narrative of how early Americans conceptualized space in relation to their own sense of identity and imagination.

As a Fellow at the Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum in Massachusetts, Cho tested her approach first on the extensive merchant archives. “The Philips Library houses the bulk of merchant correspondence: accounts, journals, logs. Really it is a historiography of early Americans entering the Pacific Ocean,” she said. “And I found a lot of evidence that merchants were fearful to travel there because it was still so unknown and elusive.” Although the merchant records heavily inform Cho’s research, she wants to challenge the dominant narrative that only scientific and commercial knowledge contributed to how people understood the ocean.

“I’m more interested in what happens when science and commerce have to be part of the larger social and cultural fabric,” she said. “What happens when instead of serving a very specific and small community, these forms of knowledge have to serve the broader public?” Contrary to what explorers like Captain Cook might have wanted people to believe, everything was not decided about the Pacific and the islands upon their initial discovery. Early American sailors, who spent most of their lives on the water and possessed nuanced understandings of the geography, have only recently begun to be appreciated as producers of knowledge. Through inserting sailors into her research, a more inclusive public imagination of the Pacific begins to take form.

“It is not down on any map; true places never are,” writes Herman Melville in Moby Dick. The “It” in Cho’s research can be conceived as the missing voices in the archive. Pushing back against the assumption that the written and visual representations of the Pacific Ocean are fixed is one of Cho’s main goals. By rewriting the history of the early republic from rather than to the Pacific Ocean, Cho reframes the Pacific as a piecemeal and fluctuating space, prioritizing knowledge formed outside the traditional cohesive narrative.