Few would take exception to the assertion that the cuisines of the Middle East offer a spectrum of delightful dishes for formal and mundane meal experiences. What is less known is the deep literary interest in food and cooking in the region centuries before the European culinary expansion in the 18th century.

In the world of writing before print, the known global corpus of dedicated literature on food and cooking remains slim. As a specialist in “premodern Middle East,” I am delighted to share that the historical archive of writing on food and cooking in the dominant languages of the Middle East (Arabic, Persian, Turkish) is embarrassingly rich in both volume and texture. As the scholar and gourmet cook Charles Perry has put it, “there are more cookbooks in Arabic from before 1400 than in the rest of the world’s languages put together.”

Let’s scratch the surface by focusing on a cookbook from the 10th century, whose author we barely know beyond his name. Ibn Sayyar al-Warraq’s Cookbook was written for an unknown patron in Baghdad. (An impressive critical edition, translation and study of the book is provided by Nawal Nasrallah, The Annals of the Caliphs’ Kitchens: Ibn Sayyār Al-Warrāq’s Tenth-Century Baghdadi Cookbook [Leiden: Brill, 2014], from which I quote.) It is divided into 132 uneven chapters, which include a substantial discussion of diet, health and decorum in several chapters and more than 600 recipes that promise to whet the appetite of the curious. The compendium highlights established as well as avant-garde dishes “cooked for kings, caliphs, lords, and dignitaries,” reflecting the cosmopolitan taste-palette of its author’s world.

Life in the medieval Middle East

My students and I very much enjoy discussing the larger context that made the writing of this cookbook possible in the first place. The lure of its recipes aside, the text is an archeological site of a scantily veiled world of scholarly activity and associated cultural efflorescence from the ninth century onward. Aided by the local production of paper and imperial patronage, many thousands of scholars, enthusiasts, professionals, literary figures, talented artists and others busied themselves with scholarship and literature. They translated a large volume of books from Greek, Persian, Syriac and other languages into Arabic, reclassified existing knowledge and added their own original compositions in all sorts of disciplines: sciences, philosophy, medicine, humanistic subjects, botany, zoology, poetry, theology and law.

On the farm, another revolution was taking place about the same time. The volume of ingredients and the complexity of dishes in the Cookbook demonstrate the full impact of a “green revolution” from the ninth century onward. In the mutual cycle of labor and benefit, the increased agricultural production helped urban growth, and urban growth incentivized more organized and profitable farming practices and crops. Trade networks sustained demand and supply, regularized exchange and encouraged the spread of new crops to regions far from their native lands. Hundreds of new crops showed up not only in urban markets from the Indus valley to Cordoba but were also locally produced.

The agricultural productivity was due to the improved imperial infrastructure, irrigation technologies, market regulations and taxation practices. An ambitious entrepreneurial agricultural aristocracy advanced the knowledge of farming and appreciated the value of rational management of farmlands for finding new ways of better and more diverse cultivation. The arduous work of the never properly acknowledged farmers, who were regularly free peasant families but occasionally plantation slaves (such as in the Lower Iraq in the eighth and ninth centuries), constituted the backbone of a robust agricultural production. One of the available farming manuals, The Nabataean Agriculture of Ibn Wahshiyya in the 10th century, illustrates the complexity and precarity of this balance.

Who’s at the table?

Before raising the reader’s eyebrow, I must temper the emerging rosy picture with a reality check. At the dinner table as well as in the farm, the difference between the haves and have-nots was stark. Ibn Sayyar’s société (which included rulers, high-level administrators, members of scholarly and literary circles, military commanders, the urban well-to-do, land-owning aristocracy and similar others) did enjoy a “global cuisine,” featuring a wide spectrum of dishes from high and low culinary traditions of the known inhabited world. At the same time, however, a large swath of people — those who lived under the conditions of urban poverty, peasants, daily laborers, artisans, small merchants and anyone living in rural areas and not on trade routes — carried the burden of production but rarely cultivated the benefit.

One must note that the author prefers to remain unresponsive to this disparity. For better or worse, Ibn Sayyar is unconcerned with the most filling or most economical food, and instead centers what is healthy, leisurely and pleasurable. He directs his reader’s attention to manner and style (of cooking, presenting, serving, eating, discussing, etc.), irrespective of function. Moreover, by the mere fact of writing about the subject, Ibn Sayyar transforms foodways into a battleground in which sociocultural identities are created and negotiated. Consequently, the book, beyond its role as guide to the actual practice of cooking and dining, exposes the class-specific nature of taste.

It would be unsatisfying, however, to suggest that cookbooks were a tactless display of wealth and power. Ibn Sayyar seeks to discipline his reader following a particular moral and esthetic worldview. He wants to mold a “gentleman” with “worldly” moral and esthetic values. The regulated and carefully defined meal experience (preparation, presentation, and consumption of a meal; dinner companions; table manners; conversation around the dinner table location; time) provided a path to self-formation and constituted a “system of communication” that marked the difference between Ibn Sayyar’s worldly elite and the larger society. The ethics and esthetics of propriety regulated the experience of the meal as part of disciplining the body in both senses of the word: self-cultivation and the regulation of society according to a particular taste preference. For this reason, preparing for Ibn Sayyar’s dinner was a major undertaking:

For the accomplished friend or the perceptive boon companion cleanliness of hands and nails is of utmost importance. He ought to keep a regular regimen of trimming the nails, cleaning between the fingers, and washing his hands and wrists before praying and eating. He should look agreeable; skin radiating with fragrance; face, moustache, and nose, clean; and forehead, immaculate. He must clean his teeth and use Cyperus in the morning, comb his beard… It is commendable for the boon companion to be handsomely attired, wear the finest clothes that are clean at the folds and edges. He ought to pay attention to what he wears. The first layer of clothes should not be without the top layer. What is not apparent of his clothes should be spotlessly clean such as the cap, pants, drawstring, sock, his sleeve’s handkerchief, and all other similar pieces. Once he becomes fully accomplished and attains all these attributes, he will be a welcome companion and a joy to socialize with.

Similarly, the Cookbook is interested as much in ordering taste and regulating behavior as in health and overall well-being. It does so from a particular vantage point, which may be captured in the Socratic phrase “taking care of oneself.” Acknowledging Galen’s Book of Familiar Foods as his source and following the Greco-Mesopotamian dietetic and medical tradition of humors, evidently experiencing a renaissance at the time, the author discusses food as a way to maintain the human body in good balance. The bare necessity of satisfying hunger is, thus, transformed into an art that requires the knowledge of human being in flesh and spirit, the properties of the ingredients that go into the meal, and the effects of eating on the body. By the sheer knowledge and manners it demands, the act of eating becomes a site to produce inequality and distinguish the “gentleman” from both the commonfolk and the modest pious.

Reading the Cookbook, one would get the impression that foodways was a world of male figures. The majority, even most, of Ibn Sayyar’s cited individuals are male. However, when there is mention of female cooks, one does not get the impression that they were deliberately kept in the margins of food and cooking. The author cites royal females and prominent slave girls for their culinary talents and describes recipes (even “books”) by several royal women known for their culinary talents.

More tantalizing perhaps are the references to groomed boys and concubines who serve as courtesans and engage male patrons in exchanges of artistic graces, literary sparring, culinary pleasures, flirtations and sexual favors. Ibn Sayyar’s casual references to male and female slavery as well as to hetero- and homoeroticism suggest a milieu in which such practices were normalized in exclusive saloons and wealthy households. How can one miss the following patently humorous lines about fava beans full of allusions to such sensual joy?

Fava beans, like unthreaded necklace or gems in virgins’ hands, Or virgin pearls enclosed within folds of shells of emerald.

Harvested today, not a single day deferred, nor was it from hand to hand transferred.

Sweeter than slumber after a sleepless night, or a promise of a rendezvous fulfilled.

Sweeter still than when a frightened heart is secure.

I came early even before the songs of birds, And the sun like a dagger was still unsheathed,

I came with a group of promising youths:

Nobles, gluttons, opportunists, heirs to thrones, the smart, and the good-for-nothing.

We all swooped like a flock of locusts, handsomely clad and most admirably joined,

Guided by the fragrance fava bean imparted. God bless it, no more provisions you need to carry.

Cooked by the hands of the graceful ones.

An exquisite gazelle summoned us,

Bringing us red wine, as rosy as his cheeks, generously offered, of which our fill we had,

Induced by the delightful singing, splendidly delivered.

What a wonderful meal it was!

Worthy of praise is living thus, and equally worthy are those who invited us.

The good life

Ibn Sayyar’s epicureanism (the emphasis on pleasure, leisure, enjoyment of life and company) and neglect of the religious normativity of his time contrast sharply with the pious ways of life and the religious otherworldly piety that call for modesty, pious restraint and self-denial. One reads nothing substantial about daily prayer, ritual fasting, religious regulations of food, modesty or disdain for luxury and gluttony, etc. In contrast, the reader is reminded of seeking pleasure for the sake of pleasure in all sorts of activities organized around food. He seems to encourage his readers to normalize pleasure by elevating it above the pious sense of guilt through beautifying and estheticizing the enjoyment of food.

Known also as “the paper seller,” Ibn Sayyar was not a lone voice. In the surviving corpus of cookbooks, I would cite only two 13th-century authors, about whom we know next to nothing, who were also interested in “the good life”: Ibn al-Adim of Aleppo, who titled his book Reaching the Beloved through the Description of Delicious Foods and Perfumes, and one al-Baghdadi, who was convinced that the “pleasures of this world” fell into six categories: “food, drink, clothing, sex, scent, and sound.” According to him, “the most eminent and perfect of these was food; for food was the foundation of the body and the material of life.”

Read this way, cookbooks more than reveal and reproduce the Abbasid social fabric. It is not a hyperbole to suggest that cookbooks even carry a “civilizing mission.” In their anthologizing nature (such as offering a carefully selected spectrum of dishes, suggesting best practices of cooking in recipes and recommending acceptable or desirable ways of consuming food), they standardize and canonize knowledge and food practices from a particular sociocultural and literary sensibility and thus fulfill the dual role of codifying the culinary tradition and regulating practices.

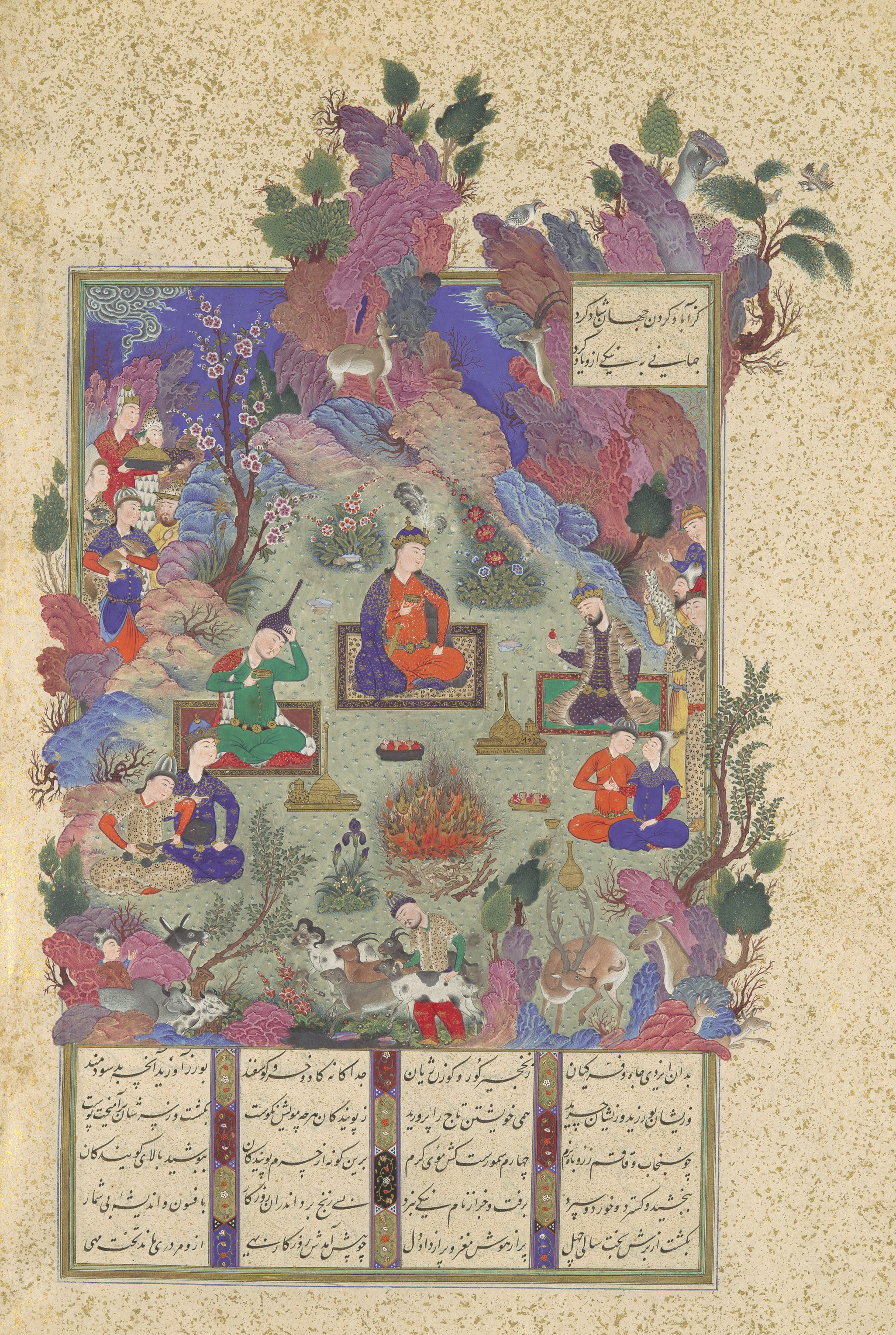

Headline image: Folio from a Falnama (The Book of Omens) of Ja’far al-Sadiq